“Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” is the most culturally relevant Costume Institute exhibit that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has produced in years.

It has already delivered the most profitable Met Gala of all time.

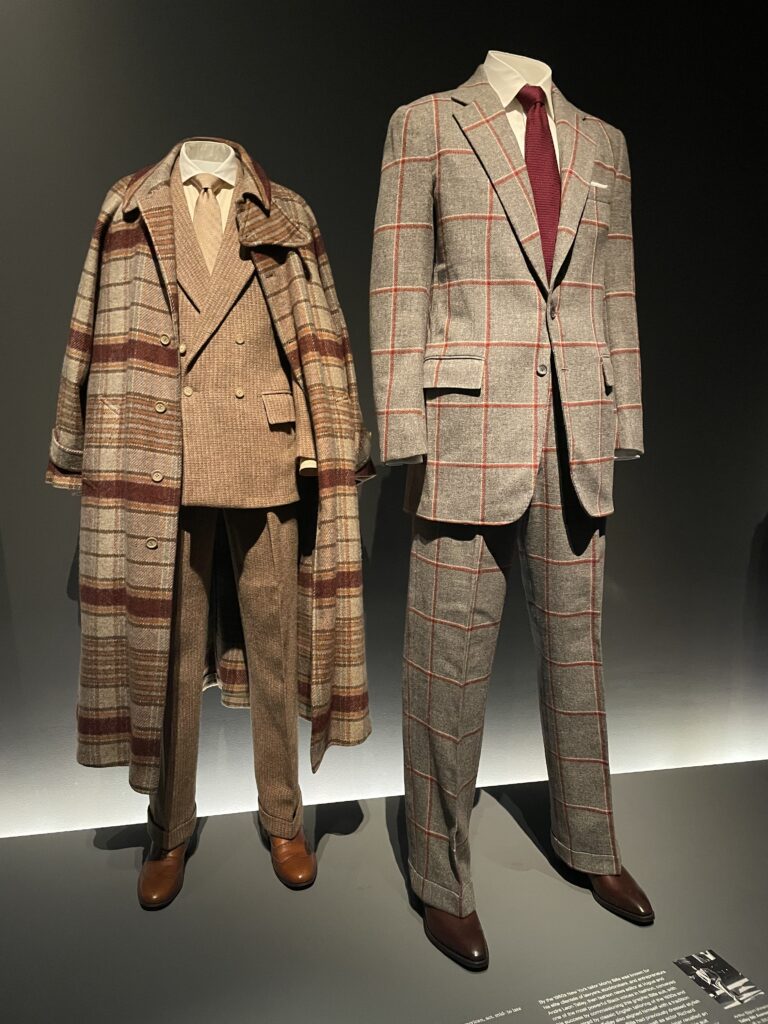

Organized into twelve sections, with each meant to encapsulate a trait of Black style, the highly anticipated exhibit traces Black fashion (with a focus on menswear) over three centuries, providing numerous clothing ensembles, paintings, photographs, and artifacts along the way. The exhibition topic is compelling given that usually, when you hear about the term “dandy”, you think about the trope popularized by Irish writer and playwright Oscar Wilde in works such as The Importance Of Being Earnest: flamboyant, dashing, and without a care in the world for anything other than leisure and pleasure. To see the Met give visitors a historical breakdown of the full timeline of the concept and its meaning for people from the African diaspora is smart — and is a conversation so very needed in contemporary culture.

Fashion, though a language through which every person conveys a message about themselves that they wish to share with the world, is even more important to the Black community. In a Western culture that has often looked for ways to disregard talent and markers of credibility from people of color, how one dresses can play even more of a crucial role in opportunities that Black people obtain. Consider a culture where, if you are a Black male and wearing a hoodie while committing the crime of walking down the street, you could be killed because someone sees you as a threat. For Black people looking to increase their social and economic fortunes, they don’t have the privilege of showing up and appearing sloppy. This is the lineage from which the Black dandy sprung.

A lineage of always needing to be on guard and conscious of how one is being perceived. A lineage requiring performances for others and appearances of being less threatening.

It is a lineage that also produces exhaustion, anger, and rage. Thus, the style of the Black dandy is also a style of protest and taking back one’s power. After all, if you have to perform for everyone else in order to be able to have a basic standard of living, then why not perform for oneself? Why let White people (both those in power and those who are not) have all the fun?

This is, in part, why early hip hop stars gravitated to luxury brands: they wanted to be able to partake in these symbols of status that others climbing the financial ladder can. It took forever for these luxury brands to love the hip hop world back — for an industry priding itself on always being ahead of the curve, fashion is so often the last one to catch on to movements — but eventually hip hop was brought into the fashion fold. And so it has been with Black people as a whole and fashion — a one-sided relationship characterized by frequent rejection now becoming more balanced and accepting. The relationship between Black people and fashion is still not perfect, by any stretch, but it is improving. This exhibit is presumably a mea culpa by both the fashion and museum spheres to rectify the many wrongs that Black creatives have endured as a result of hostility from both the fashion and art worlds over the course of time.

Given the current era we’re in – with anti-DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) initiatives becoming like kryptonite for those looking to appease a United States president engaged in (likely illegal) funding revocations to arts & culture organizations and other portions of both the US government and our society as a whole – the Costume Institute’s unique funding structure gives it a distinct advantage in that the Met requires it to raise its own money to fund exhibits and initiatives. With the Costume Institute being left to its own financial devices, it will likely be allowed a flexibility in programming that other wings of the museum accepting federal funding might not have. While “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” was decided on as a theme before the current US presidential administration took office, the Met curatorial team sure caught lightning in a bottle with the timing of this one.

Given the important statement being made, the message of the exhibit almost becomes more important than its particulars. However, there is one particular point that needs to be made: the wayfinding of “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” left a lot to be desired. After entering the exhibit hall and making one’s way through the first 3-4 categories provided by the curation team, the direction in which you’re supposed to go dissolves precipitously. You’re then left to wonder, “Am I looking at work in this category or that one?” To the casual museum attendee, this might not be as much of an issue because many in that mindset are likely there to casually observe and learn what they can in a low-key way.

But for many, an exhibition needs to bring the attendee along on a directionally comprehensive journey (aka, people need to know where they are supposed to go based on the criteria given by the institution) while giving them the knowledge necessary to feel as if they can leave – confident that they have a clear understanding of what they have just seen. The Met succeeded in its messaging, but not in its exhibition organization. Though the wayfinding has never been particularly intuitive at shows hosted by the Met’s Costume Institute, a crucial topic such as this one needs more specific guidance. In a social climate antagonistic to historical analysis specific to underrepresented groups, the hosting institution has a special responsibility to make sure that people are coming out with the correct knowledge and the timeline by which things occurred.

They might not get that knowledge anywhere else.

The Costume Institute’s “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” is open to the public for viewing through October 26, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

To subscribe to Manic Metallic‘s Substack newsletter, click here.